Saints, Mermaids & Phoenicians Contents

Cornwall's History & Legends

Print

taken from J Blight’s

The Mermaid

The

people of Zennor, in Cornwall tell the following story, which, according to them, accounts for a

singular carving on a bench-end in their Church.

The Legend

Hundreds

of years ago a very beautiful and richly attired lady attended service in Zennor

Church occasionally—now and then she went to Morvah also;—her visits were by

no means regular, —often long intervals would elapse between them.

Yet

whenever she came the people were enchanted with her good looks and sweet

singing. Although Zennor folks were remarkable for their fine pealmody,

(singing) she excelled them all; and they wondered how, after the scores of

years that they had seen her, she continued to look so young and fair. No one

knew whence she came nor whither she went; yet many watched her as far as they

could see from Tregarthen Hill.

She

took some notice of a fine young man, called Mathey Trewella, who was the best

singer in the parish. He once followed her, but he never returned; after that

she was never more seen in Zennor Church, and it might not have been known to

this day who or what she was but for the merest accident.

One

Sunday morning a vessel cast anchor about a mile from Pendower Cove; soon after

a mermaid came close alongside and hailed the ship. Rising out of the water as

far as her waist, with her yellow hair floating around her, she told the captain

that she was returning from church, and requested him to trip his anchor just

for a minute, as the fluke of it rested on the door of her dwelling, and she was

anxious to get in to her children.

Others

say that while she was out on the ocean a-fishing of a Sunday morning, the

anchor was dropped on the trap-door which gave access to her submarine abode.

Finding, on her return, how she was hindered from opening her door, she begged

the captain to have the anchor raised that she might enter her dwelling to dress

her children and be ready in time for church.

However

it may be, her polite request had a magical effect upon the sailors, for they

immediately “worked with a will,” hove anchor and set sail, not wishing to

remain a moment longer than they could help near her habitation. Sea-faring men,

who understood most about mermaids, regarded their appearance as a token that

bad luck was near at hand. It was believed they could take such shapes as suited

their purpose, and that they had often allured men to live with them.

When Zennor folks learnt that a mermaid dwelt near Pendower, and what she had told the captain, they concluded it was this sea-lady who had visited their church, and enticed Trewella to her abode. To commemorate these somewhat unusual events they had the figure she bore—when in her ocean-home—carved in holy-oak, which may still be seen.” (Ref.1.)

The Evidence.

The above is just one of the numerous mermaid legends which can be found in both Cornwall and other Celtic countries, but where do they come from?

When the Phoenicians first came to Cornwall they must have learnt to converse in order to barter. When the trading day was finished, the traders and buyers probably sat round the fire enjoying the local hospitality and exchanging tales. The Cornish no doubt had their stories, and the Phoenician’ s probably told of their great sea journeys and to add a little excitement probably claimed to have met the “tritons” as they called the mermen and other strange creatures.

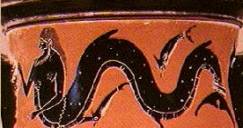

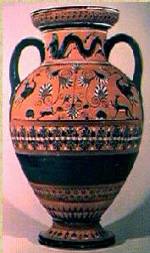

They may even have traded a vase showing a typical floral pattern and the triton

motif similar to the one on the left, found by archaeologists in Etruria one of the

Phoenician city-states and which is believed to have been made around the year

540BC.

They may even have traded a vase showing a typical floral pattern and the triton

motif similar to the one on the left, found by archaeologists in Etruria one of the

Phoenician city-states and which is believed to have been made around the year

540BC.

The Phoenicians would have set up makeshift alters in order to worship their gods El and Baal and the goddess Astarte / Asherar-yam, our lady of the sea. Little figurines such as the Bull would have been used and in the case of the goddess the symbol may have been as simple as a coin. Coins found at one of the ancient Phoenician sites have a Mermaid on them and this is believed to have been a representation of Astarte who was also linked with mother goddesses of neighbouring cultures, in her role as combined heavenly mother and earth mother. Cult statues of Baal and Astarte in many forms were left as votive offerings in shrines and sanctuaries as prayers for a good harvest and by the infertile wishing for help. It may be that the tossing of coins into fountains and Wells is a result of the goddess being put on a coin by the Phoenicians.

Many of these shrines are still to be found at the sites of springs or wells around the Mediterranean and I have visited them in both Greece and Turkey and found offerings still being left.

In Celtic tradition water was of great importance and archaeologist have found lakes and wells a great sources for finds dating from the Celtic age. In the lake on the Isle of Anglesey, objects from all parts of Briton were found that dated to the period when the Romans were driving the Celts westward. These included the usual coins, pins etc as well as Slave chains and a complete chariot. Whilst in Coventina's Well at Carrawborough, Northumberland the finds included replicas of human heads, as well as over 14,000 coins, a bronze dog and horse, glass, ceramics, bells and pins.

Strabo cites Posidonius as mentioning a "sacred precinct and pool" in a region near Toulouse in France. Treasure taken from it and later pillaged by the Roman consul Caepio in 102BC, comprised an estimated 45,000 kilograms of gold and nearly 50,000 kilogrammes of silver.

Spirits have always been associated with springs and wells from the earliest times, and the Druids used sources of water as entrances to Other worlds. In ancient stories such as "Branwen Daughter of Llyr" a giant emerges from the lake with a cauldron on his back whilst a more famous tale is of the lady of the lake giving the sword Excalibur to Arthur.

In ancient Gaul the custodian of the healing spring was a fertility goddess, always beautiful, sometimes dangerous, and these female deities have metamorphosed over time into the faeries of popular tradition.

“Ladywells” are often connected with sightings of a strange lady, a ghostly figure, perhaps of the displaced well spirit or priestess. Whilst the water spirits in Gaul were known as 'Niskas' * or 'Peisgi', the word may derive from Old Celtic 'peiskos' or Latin 'piscos', both meaning fish. In Cornwall the strange lady turned into a 'mermaid' who enticed men into her underwater world.

In Cornwall there are a number of Wells which are still used by people seeking help, and on a recent visit to Alsia Well near St Buryan I found that votive offerings including coins had been left, the Phoenecian custom having been adopted by the Cornish as part of their own religion and the mermaid legends passed down through the ages.

*Note.

Sir

F. Palgrave in an article entittled the "Popular Mythology of the

Middle Ages" which was published in "Quarterly Review No 44 in 1820

says:- "The Nixie... are in most respects like the Cornish Mermaid."

REFERENCE

“Traditions and Hearthside Stories 0f West Cornwall, 2nd Series”, Edited by William Bottrell, First Published by the Author in 1873.

If you would like to contact the author of this work please send an e-mail to the address below.

george@penhalvean.freeserve.co.uk